April is the season when boats coming from the Caribbean start making their way to the Mediterranean, facing the west-east Atlantic crossing, the most challenging and most demanding crossing, which only a few amateur sailors decide to tackle.

Today, we meet Omero Moretti, a skipper for 35 years, both for passion and work, and has embarked on an Atlantic crossing 39 times as of today.

Well, it's undoubtedly harder, more demanding and more technical than the Atlantic crossing to the Caribbean, yet it's the one that brings me back home and the one that allows me to appreciate the boat's strength and character to the full. That is why it has always been my favourite crossing.

I usually follow the return crossing route: this takes me very far north, around 34°- 38°. At these latitudes, the ocean begins to be challenging, but that's where you have to find the western circulations that can give you a fair wind to sail east. Further south, we are still in the trade wind, but instead of having it in our favour, as it is on average during the outward voyage, it is contrary. And sailing upwind in the ocean, with a three-metre wave when the going is good, is not very pleasant.

Many follow a more southerly route, starting a little later and stocking up on diesel. But apart from the wind, I also like to go north to stop off in the Azores, beautiful, remote islands where a few-day stay is both pleasant and useful. There is always something to repair or tune-up before tackling the last leg to Gibraltar.

There are two things I often tell those asking me how to prep for an Atlantic crossing on a sailing boat. The very first I'd say is that the Atlantic crossing, nowadays, is a treat that many more people can achieve than one might think. The second thing is that it is men who cross the ocean, not boats.

The fact that sailing across the ocean today is more manageable than even just a few decades ago is a trivial statement. GPS, satellites and equipment of all kinds make sailing accessible to even the most inexperienced sailors. There's no need to go too far back in time, just thinking of my first sailing years: I didn't have a GPS onboard, it wasn't widespread for leisure boats, and commercial GPS were prohibitively expensive for me. I did everything with a sextant, an astronomy book and the radio (which I used to call the ships I encountered on the way to get confirmation of their estimated position). Downloading weather charts was also time-consuming and not always successful, with weather faxes depending on propagation.

Today I have three GPSs on board, internet and satellite connections for downloading weather (although I still use the radio for my pleasure), and I generally use the sextant only for lecturing the more willing crew.

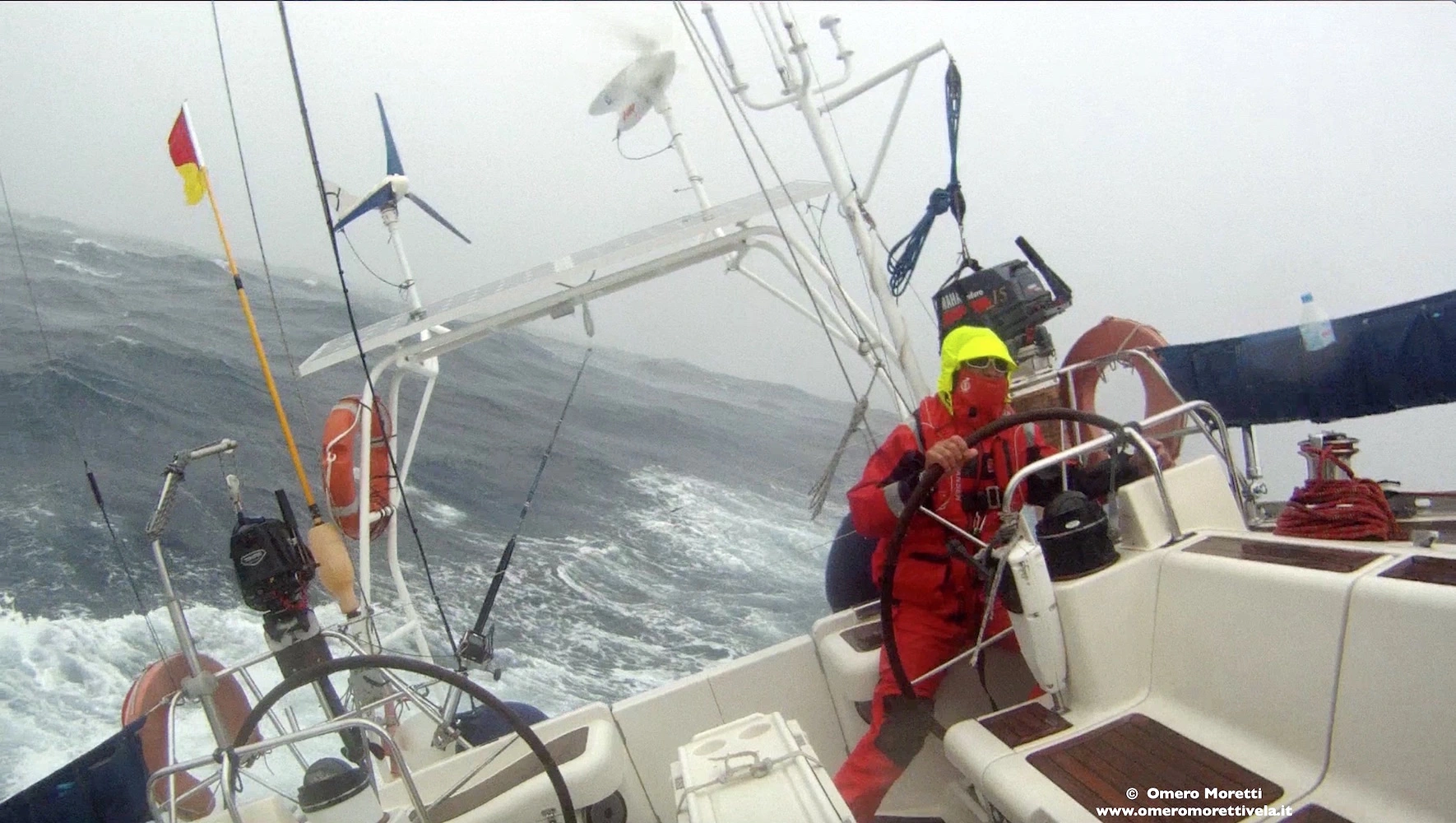

Omero's crew on their way to the Azores in the mid-Atlantic

That said, some aspects have not changed at all over time.

The first - and the reason why I say it's men who cross, and not boats - is that set sail with 3,000 miles ahead of you still means heading into the unknown, even if that unknown has been fully mapped and covered by satellite signals.

We will only have weather forecasts for a few days, and then we will have to take what comes. Assistance from the land is generally available only for a few hundred miles, and then you will need to fend for yourself no matter what happens. Indeed, you now have the luxury of accessing instruments and tools to communicate and feel less alone. Still, ultimately only you can make the necessary decision for your boat and the crew you're sailing with.

Over the years, on my 39 Atlantic crossings, teaching people to leave the dock with awareness has been the most crucial part of my work. I also talk a lot about these aspects in my book, Il mestiere del mare (Working at sea), published by Il Frangente. Sorry for the publicity, but they really are topics that would take many pages!

Let's say that awareness and a little bit of sea experience are the fundamental prerequisites for those who want to tackle a crossing with their boat. Then we can talk about how to get ready and how to prepare your boat. Writing about getting ready, to me, already is challenging. There's one thing I've learned in 35 years at sea: There are too many variables to be able to say in good conscience, "that's how you need to prepare for...". So take advice and best practices as general guidelines you can approximately follow but combine it with your experience and skills.

Let me explain. Nowadays, with 70-foot carbon prototypes with foils, you can do a roaring 50: but none of us is as skilled an athlete as one of the Vendee Globe sailors, nor do we have that sort of organisation behind us. So as a first consideration, I would say you need to be able to manage your boat, from manoeuvres to repairs: it's useless to talk about an excellent theory if you will never be able to apply it. That's just the best way never to get going.

I believe that the essential technical checks should be those concerning those parts most heavily used: the mast and rigging, the rudder blade, the stanchion and the sea intakes. Halyards are also subject to a lot of stress during long voyages, often at the same speed, so it is essential to check them, change them if necessary and certainly prepare one that has already been passed into the mast in case it breaks.

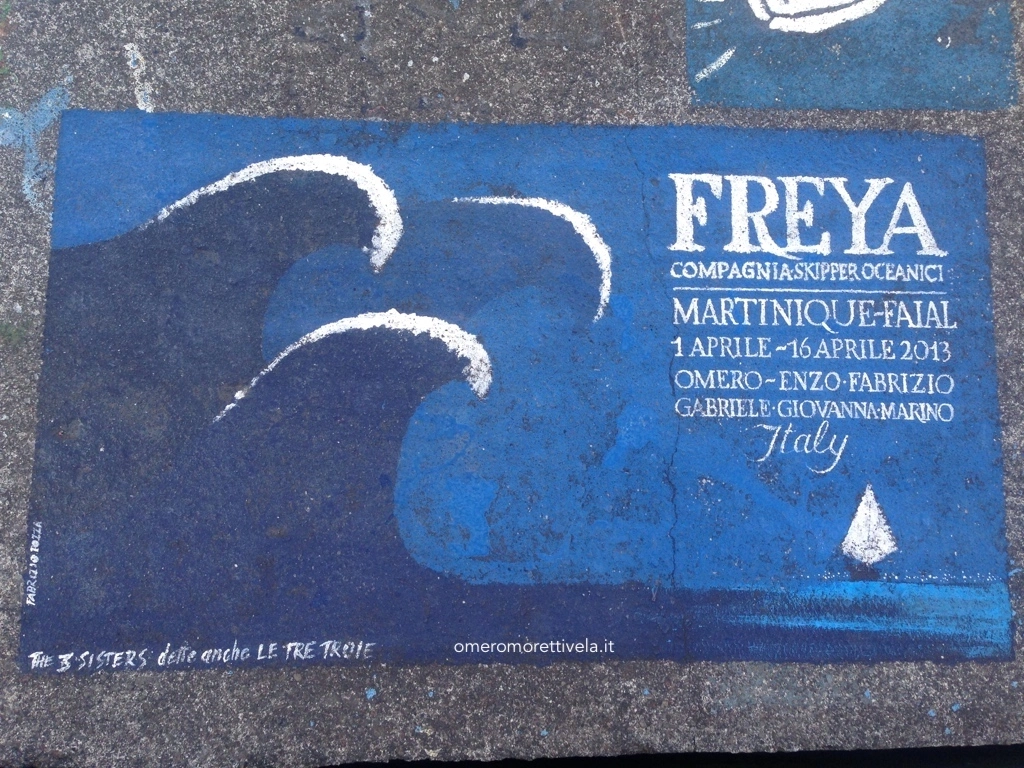

This reminds me of one of my most favourite motto: two of everything. Something the ocean taught me and that I carry with me after countless breakages. The last one that gave me a hard time was the breakage of one of the two forestays during coming back on an Atlantic crossing. We were a thousand miles away from everything, but luckily Freya, my boat, also has two stays.

If you don't sail alone, spend some time preparing your crew. Sail together first. Get to know each other and make sure the roles are as clear as possible. Once you are in the middle of the sea, there is one and only one captain, there must be discipline, and it is a matter of safety that it should be so.

This is even more apparent on a west-eastern crossing, where the boat can encounter even more significant challenges, and often so is your crew. When I sail in the North Atlantic, I reinforce the portholes with plexiglass from the outside, and I stow the anchor and chain in the bilge to better balance the weights. In short, it takes technique, and you can't just improvise.

Sunset in the ocean

How experienced do you need to be to embark on an Atlantic crossing?

I often say that an Atlantic crossing should be the end of a journey, not the starting point. I know that nowadays, with everything seeming more accessible and comfortable and with so many videos often showing only part of the story, many people approach this experience without having sailed at least a little bit first.

Crossing the Atlantic can not only be dangerous, but also, if you have not internalised what it means to really sail the sea, you risk living half a crossing with the anxiety of missing your flight when you arrive, or worse, of getting bored, instead of enjoying the ride.

If you’re interested to learn more about Omero and his trips, sail away on his Instagram account @omeromoretti or visit his website omeromorettivela.it

Fair winds and following seas!

Our regular email newsletters include information about our boats, holiday ideas, destination insights and cultural briefings. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll treat your data with respect, never passing on your details to third parties. Find full details of our data management in our Privacy policy page

By signing up, I agree to Sailogy's T&C's and Privacy policy

Looking for inspiration for your next sailing holiday? Packed with insights on trending sailing destinations plus stories from expert sailors and first-timers, our brand new digital magazine - Magister Navis - will guide your way to your next sail.

View magazine